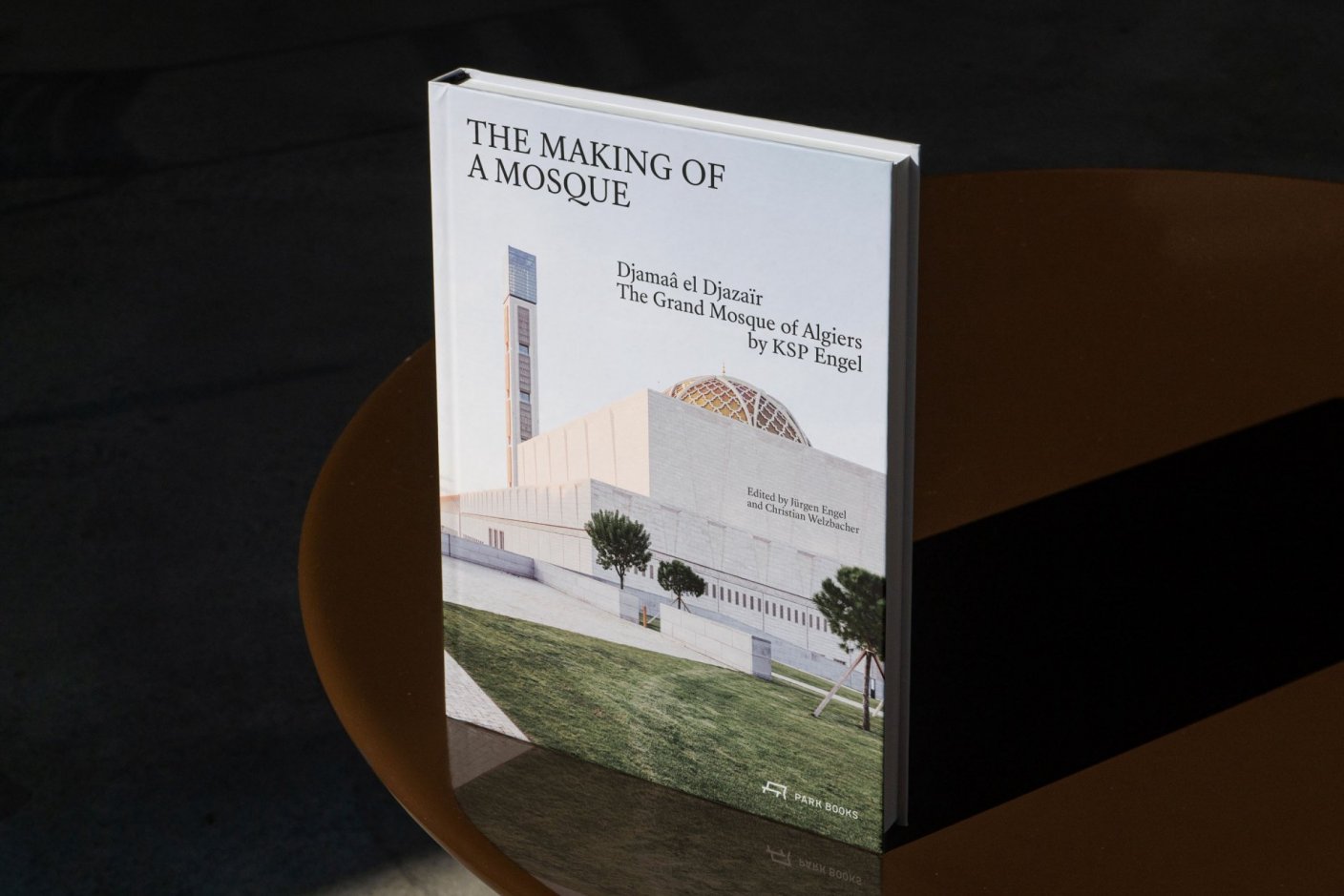

In 2011, the foundation stone was laid in the Algerian capital of Algiers or the third-largest mosque in the world. Two years ago, it was finally completed. The mosque was designed and planned by Jürgen Engel and his team at KSP Engel. The story Engel has to tell about it is quite amazing. From the initial research on mosque designs to the linking of Islamic tradition with modern architecture, through to work on an intercultural construction site: All these form the subject of a book now being published by Park Books, Zurich, under the title “The Making of a Mosque by KSP Engel”. In an interview with hr-iNFO, Jürgen Engel talks about the idiosyncrasies of the project and what a German architect can learn from building a mosque.

Christoph Scheffer:

You are best known in Frankfurt for designing sober, modern office buildings. So what was it that so fascinated you that you decided to build a mosque?

Jürgen Engel:

We have always worked on cultural buildings and have in fact built quite a few of them. Among others, we masterminded the Chinese National Library in Beijing and a few museums in China. We also designed the memorial in Bergen-Belsen. These are likewise contemplative cultural edifices that can certainly be very emotional.

“The sheer size of the mosque inspires reverence and is very moving.”

Christoph Scheffer:

How did you approach the specifications in question, which stemmed partly from religion and Islamic tradition?

Jürgen Engel:

A building project such as this is, first and foremost, a wonderful prerequisite for learning. Every competition we participate in within another culture is always a major and interesting task for us, because we have to not only address the local culture and the site-specific conditions, but also tackle the building itself, on top of which there is the religious aspect. That is always one of the most enjoyable tasks for us, to be quite honest. We did plenty of research, of course, and sought external help. I visited mosques like the one in Cordoba, for example, which I found really interesting and fascinating. The hall-of-pillars typology for a sacred building was something I was particularly struck by. It simply means there is no hierarchy in the inside space. In other words, the interior is a large hall where people gather and are democratically equal. Of course, we also sought advice on this and acquired a great deal of knowledge about the right visual idiom and ornamentation.

“The interior is a large hall where people gather and are democratically equal. It simply means there is no hierarchy in the inside space.”

Christoph Scheffer:

How did this place influence you? In what ways did you allow the place to affect you and how did the idea, the shape of this mosque, come to you, so to speak?

Jürgen Engel:

Algiers is a wonderful city situated in a crescent-shaped bay and opening onto the sea. In front of it, there are ships waiting to enter the harbor. There is something protective about the setting. In architectural terms, too, the city has a mix of the Parisian Hausmann era, fin de siècle, colonial style, and buildings by Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer.

The site itself can be considered an extension of the city, and for that reason we viewed and designed the mosque partly as a catalyst for urban development. To that end, we considered how we could erect an elegant, strong building in this setting that would accommodate around 120,000 people for Friday prayers. In addition, we also took inspiration from the country’s flora and fauna, and that’s why we opted for a floral motif for the columns. This is how the idea for the calla column came about, which has its origins in the calla blossom and characterizes the entire grounds of the mosque. Not least, we looked into the tradition of the country. The Maghrebian mosque traditionally has an asymmetrically positioned minaret in the form of a tower. We locked into this tradition and ultimately designed a kind of skyscraper based on a square ground plan. At a height of 265 meters, the tower of the minaret is the tallest building in Africa. I can barely describe the dimensions of the complex in words – you really have to experience it for yourself.

“When we planned the mosque, we thought about how to build an elegant, strong building that could also function as a new quarter of the city.”

Christoph Scheffer:

How did you personally feel when you entered the finished space for the first time?

Jürgen Engel:

That’s an interesting question. In the beginning, everything is just a structure, and you see these enormous foundations with the sea behind them. When the mosque was finished, in other words when the interior was sufficiently advanced that you could really feel it, that was very uplifting. Even the sheer size of the mosque inspires reverence and I found it very moving. These are places that, when you enter them, you come to a stop and are suddenly focused only on yourself and the place. You don’t think about anything else and precisely that is what goes to make the quality of such buildings.

“The construction site was like one huge workshop where not only was a building under construction, but there was also cooking and living going on along the sidelines.”

Christoph Scheffer:

In the book you published together with the author Christian Welzbacher in 2022, essays, interviews, design drawings, and sketches tell the story of construction from an intercultural perspective. What did you learn about an intercultural building site? What made the collaboration so special?

Jürgen Engel:

Many different nationalities came together on the building site. We had German architects and planners, a Chinese construction firm, Algerian workers, and Canadian project managers all on site. Now of course that great mix gave rise to some pretty entertaining stories: The Chinese, for example, planted vegetable gardens in all the free spaces on the site. They had their own gardeners, who made sure the beds were all well-tended. That was practically also the food eaten by the construction workers on the site. It was exciting for us to see how life went on at the construction site.

There was also a lot of improvisation, which was certainly very effective: For example, the construction workers made the spacers themselves from small concrete blocks. Here in Germany, we normally use industrially mass-produced items made of plastic. There, however, many things were handmade, because not all the materials and tools were available at all times. The willingness and ability to improvise, paired with pragmatism and creativity, were really impressive and always very enriching. This construction site was definitely a new and interesting experience.

This article is an excerpt from a conversation between Jürgen Engel and Christoph Scheffer broadcast on hr-iNFO Kultur. The full interview can be found in the ARD Audiothek, beginning at minute 06:35.

The book on the construction of the mosque, edited by Jürgen Engel and Christian Welzbacher, came out under the title “The Making of a Mosque: Djamaâ el-Djazaïr – The Grand Mosque of Algiers by KSP Engel” at the end of May 2022. It is published by Park Books, Zurich, and is available in German, English, and French here.

Jürgen Engel

Principal