“In symbolic terms this religious project has inspired the entire nation and it serves as a source of inspiration throughout the world.”

Multicultural Project

The entire planning process for the mosque complex and its minaret was the result of a collaboration between Algerian and international experts. This applied not only to the space allocation program and the complex’s symbolic shape, which were devised as part of a cooperation between the religious authorities, Islam scholars, and historians of art and culture, but also to the construction of the mosque itself. During the early phase of planning, KSP Engel and Krebs+Kiefer invited well-respected engineers and seismologists to Algiers to discuss the chosen solutions with one another. The China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) was tasked with the actual realization of the Djamaâ el-Djazaïr. The project was managed by Dessau of Canada. The entire project also sets completely new standards in terms of earthquake proofing and was consequently followed with great interest by the world’s experts on the subject – as a multi-faceted “lighthouse” in the Bay of Algiers. The Great Mosque is not only the city’s new religious center, it also serves as a new landmark. The prayer hall represents the heart of the mosque and can accommodate up to 36,000 believers.

Shape, Aesthetics, Transparency

The 265-meter-high minaret is the ensemble’s vertical anchor point – the lighthouse, so to speak, visible from afar. It looks out over an extensive religious and cultural quarter on the shores of the Bay of Algiers which surrounds the new building that is the Great Mosque of Algiers, currently the third-largest mosque in the world (after the pilgrimage sites of Mecca and Medina). With its slender tower stretching up into the heavens, the shape of the Djamaâ el-Djazaïr brings to mind other historical role models. Its angular, cuboid footprint references a typology which, historically speaking, is to be found in the Maghreb region of North Africa and in Andalusia. The most famous example of this is the “Giralda” belltower in Seville’s present-day cathedral. With its recessed viewing deck looking out over the city and the sea, the spire with its setback top story is enveloped in glass and open to the public and to all visitors.

That said, in Algiers the historical stone constructions have been reinterpreted and translated into a harmonious and contemporary combination of a trio of steel, glass and concrete. Four corner towers braced crosswise with steel girders rise up heavenwards over the entire height of the minaret building. On the stories without cross bracing, this structure allows for open halls with glass façades on all sides. The center of the tower has been left free of fixtures and fittings and of loadbearing elements of any kind. Accordingly, both visitors and users are treated to an unobscured view through the entire interior of the minaret out across the countryside, the city, and the sea. From the outset, this kind of transparency, and it is unusual in a high-rise of these proportions, with its open layout, formed one of the core elements of the design.

Building as Symbol

The structure of the tower’s shaft and the façade can be seen as a multifaceted and symbolic shape that references the Koran and the principles underlying Islam – the Five Pillars of Islam. There are five sections, each with five stories and a height between floors of 5.50 meters, something visibly underscored by the difference in materials on the façade. Some are clad with latticework featuring a restrained design known as mashrabiya, which acts as a shading element. Positioned between these decorated areas, and in notable contrast to them, are the glazed sections of the total of five viewing levels (sky lobbies). They act as open halls, vantage points or places for visitors to linger; they can also be greened. At the same time, they act as distribution concourses for the various different uses. As a hybrid high-rise, the minaret has a public role, e.g., it is home to a Museum of Islamic Art and History and boasts a viewing platform in its glass-covered tip. Furthermore, the tower also houses administrative functions and is home to a research center. Since some of the minaret’s uses are public ones, it was crucial to bundle pedestrian flows inside it and provide clear points of orientation. This was achieved by locating the vertical access shafts (elevators and staircases) as well as the safety systems in the corner towers. The interiors, devoid of any other pillars – in a similar vein to a conventional high-rise – can be used very flexibly. Accordingly, the exhibition areas can be sub-divided as required, which is also the case with the office and administration space in the tower. The latter can be used both for open-plan offices and for smaller units, depending on requirements. Accordingly, the minaret high-rise represents part of a religious edifice that incorporates certain secular usages.

“In terms of function, this is a hybrid high-rise which includes a wealth of different functions.”

Context and function of the building

KSP Engel was commissioned to realize the building after its design proposal won the international competition in 2008. The task at hand was not only to erect a national mosque. At the same time, the brief included undertaking urban planning to interface the major new residential and business district with downtown Algiers. Designed for up to 120,000 visitors, Djamaâ el-Djazaïr serves as precisely that interconnecting link, something also expressed in the large number of its possible uses. The ensemble includes a theological college, residential buildings, the administration, a museum, a place of prayer and of withdrawal, parks, a viewing platform, a library, and a film archive. These functions are distributed over several different sections of the ensemble, including the hybrid high-rise of the minaret.

Façades

The minaret’s exterior brings together various different kinds of façade. The corner towers are clad with beige-white travertine panels from Italian quarries. The mashrabiya were cast from fiber-reinforced concrete dyed an earthen color. They are located behind a curtainwall which stands out prominently level with the sky lobbies and at the upper edge of the tower (soummah). The large glass panels on the transparent tip are mounted on a steel frame measuring a total of 45 meters in height. Depending on the light, they look extremely transparent or resemble a closed shroud.

Construction and structural engineering

For the client, durability played an important role in the Djamaâ el-Djazaïr project from the very outset. This applied not only to the materials used but also and very particularly to the construction of every single element, as Algeria lies in a region where earthquakes pose a serious threat. With the minaret high-rise, this fact impacted logically on countless aspects of the structural engineering and thus on decisions jointly taken by KSP Engel and Krebs+Kiefer, the engineers involved in the project. The very first consideration was to construct a tower that was extremely slender and elegant rising up from a square footprint measuring 28 x 28 meters. The proportions of the latter reference the complex as a whole while also making it necessary to create such an unusually high building. The ratio of breadth to height is 1:10.

“Technically speaking, what we are talking about is an edifice that sets new building standards in a region threatened by earthquakes.”

Earthquake resistance

The next construction-related decision related to the loadbearing structure. Instead of opting for a central core, the decision was taken to build four corner towers made of reinforced concrete. These are braced by means of something known as a Vierendeel loadbearing structure with striking x-shaped cross bracing. The resulting structure is an intrinsically rigid building that is nevertheless flexible enough to withstand intermittent earthquake shocks and can absorb the related considerable vibrations to the entire tower.

The Great Mosque forms a symbiosis between the Maghreb building tradition and an understanding of architecture rooted in the present-day. Elements such as the calla columns or the minaret as a slender high-rise are innovative interpretations of historical architectural typologies. As a modern Friday mosque, Djamaâ el-Djazaïr not only represents the focal point of religious, civic, and social life, but also functions as a catalyst for urban development in eastern Algiers. What has been produced here is a new Maghreb architecture that is international in reach.

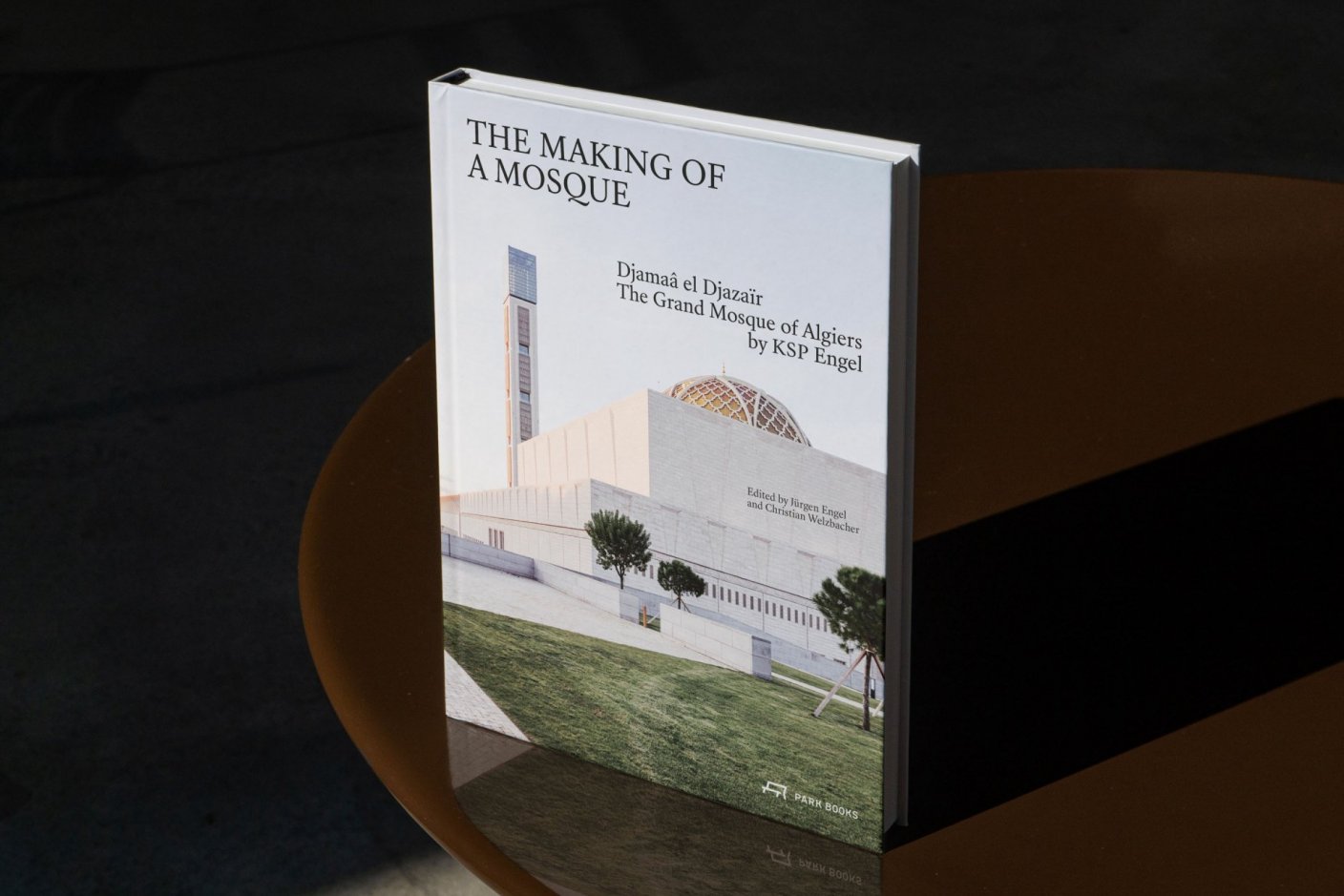

Entitled “The Making of a Mosque: Djamaâ el-Djazaïr – Die Große Moschee Algier von KSP Engel”, the book on the building of the mosque by Jürgen Engel and Christian Welzbacher was published by Park Books Zurich in German, English and French at the end of May 2022, and is available here.

Jürgen Engel

Principal