Building information modeling is regarded as the method of planning of the future. KSP Engel has already gained plenty of experience of the advantages of using it - and the challenges involved.

For architects, working digitally is nothing new. The first CAD programs began replacing T-squares as long ago as the 1980s, but it was not until early 2017 that Federal Minister of Transport Alexander Dobrindt presented the “Bauen 4.0” masterplan for infrastructure projects, which is intended to advance the use of building information modeling (BIM) as the digital method of planning of the future.

With regard to structural engineering too, the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (BBR) is spearheading the introduction of and research into BIM in Germany. The Federal Ministry for Building (BMUB) has instructed that in future, government structural engineering projects worth upwards of EUR 5 million must be checked for their suitability for BIM. This means that with regard to German construction and architecture, the government has now started to prioritize something that in other countries has long since happened: The switch from 2D design based on analog prints to 3D-based design in which digital building models serve data transfer. Talking about his experiences working for Foster and Partners in London, Sebastian Schöll, Managing Director and Partner at KSP Engel, says that he was already working there with BIM 15 years ago. In Germany, on the other hand, it was the building industry, as well as the facility management sector, that initiated developments leading to BIM. “We were always being asked for 3D models,” he adds. Given this scenario, in 2011 KSP Engel decided to gain initial experience by applying BIM to the “Taunusanlage 11” project.

Defining our own standards

Frank Rudolph, head BIM administrator for all branches of KSP Engel played a leading role in the introduction of the new planning method, and remembers the pilot project very well. “Most of all we wanted to gain experience with 3D building modelling,” he says. Together with a small team that included Benjamin Agyemang, BIM administrator in the Frankfurt office, a lot of effort was put into familiarizing themselves with the modelling software Revit, he recalls. However, to be able to make optimum use of the new planning method, relevant structures and regulations had to be put in place. “First of all, we drew up standards of our own for using BIM,” Frank Rudolph says, describing the initial steps. And Benjamin Agyemang adds: “We also put a lot of thought into how to shape the standards such that not only the basic planning but also the quantity surveying and budgeting departments, not to mention others as well, also benefit from modelling.”

They ultimately managed to define standards such as the naming conventions so that approx. 90 percent of all the construction parts used in 3D modelling can easily be linked to the company’s databases, for example that for construction part costs. This ensures the largely smooth transfer of data from one service phase to Service Phase to the next.

A digital planning method using BIM thus also ensures close interaction between the Design, Planning, and other departments such as Construction Management. The digital building models facilitate quantity surveying for the relevant costing stage (budget, cost estimate, cost calculation). Clients benefit from the great precision regarding the quantities needed at relevant planning stages, and as such from greater cost certainty.

Using programs such as ‘RIB iTwo’, the one Construction Management employs for tendering, the award of contracts, and accounting, the digital data can be evaluated accurately and the costs updated quickly, should changes be made to the design. They enable architects and clients to quickly gain a clear idea of costs and quantities, and make it easier to draw up service specifications. KSP Engel is one of the first companies to consistently implement the integrated use of 3D models for planning and construction.

However, according to Frank Rudolph, the next step is already imminent: 5D planning. Alongside the 3D business models, this will also integrate the factors costs and time management in the digital planning process. As Agyemang says though, at the moment it is still not possible to do without plans, adding that the company is somewhere between the analog 2D past and the vision of exclusively digital 3D building modelling.

More efficiency and fewer errors

At KSP Engel, it was the Munich office that pioneered the introduction of BIM. Christian Eichinger is Munich’s Managing Director. He sees many advantages in the use of BIM. KSP Engel, he says, now lands contracts specifically on account of its great BIM expertise and experience. Furthermore, there had been an enormous increase in planning efficiency, and what had previously been very laborious quantity surveying and cost estimation is now considerably easier. BIM also affords clients greater cost certainty, as when amendments are made to designs the cost estimate is automatically updated. Drawing up plans is also far faster once the 3D model had been constructed.

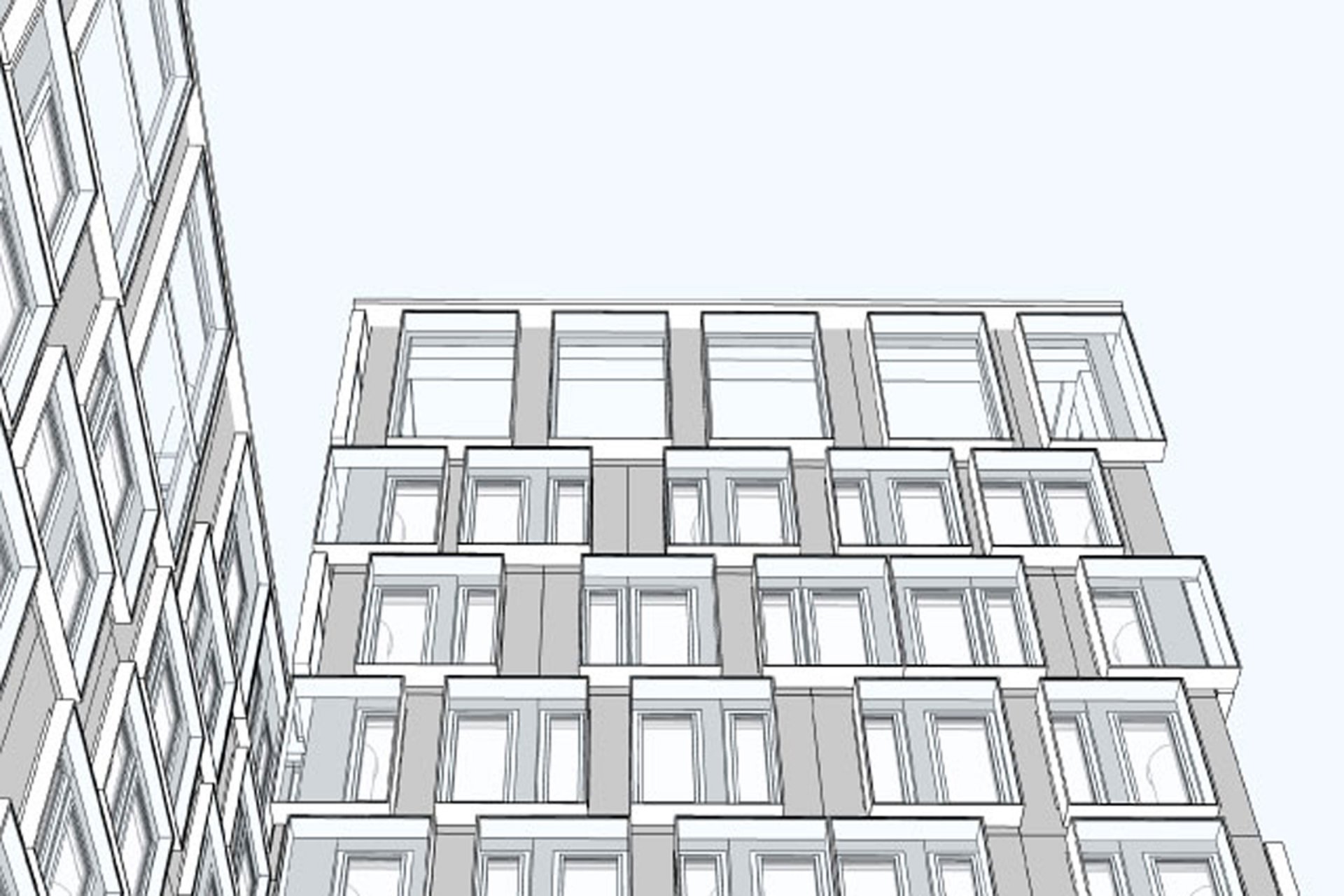

However, Christian Eichinger points out that 3D modelling is initially more laborious than a 2D drawing. “The additional effort pays off if we land a contract above HOIA Service Phase 4,” he says. The greatest gains are with stages 5 to 7, something Sebastian Schöll bears out. From his point of view, design coherence is the value added that the use of BIM offers. This is primarily the result of literally being able to see errors in the 3D model. Automated error search based on personally defined rules, for example the checking of escape route lengths, which BIM makes possible, play a role here. KSP Engel is currently planning a whole series of BIM projects of different size and function, among them designing the new German Embassy in Algiers, revitalizing and converting the “Hochhaus am Park” high-rise in Frankfurt, and building new housing in Worringer Strasse in Düsseldorf.

Siemens Campus Erlangen, an example project

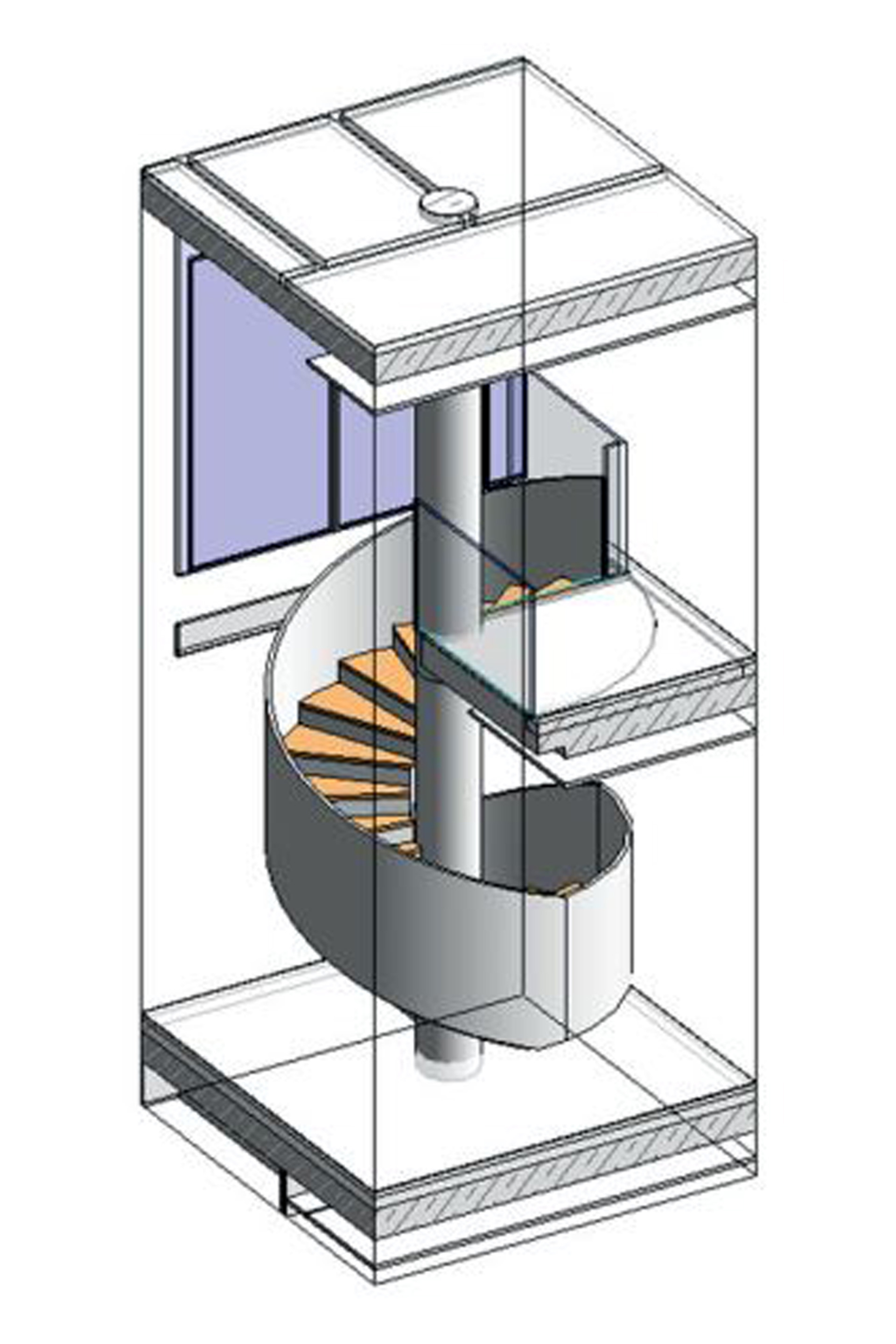

The design of the “M115” reference building for the Siemens Campus in Erlangen was one of the projects for which BIM to a large extent was used . It served as the basis for all other buildings of this type on the campus. Alongside 3D building modeling and plan development, renderings, and error checks based on the model, KSP Engel also coordinated the integration and testing of the specialist planners’ various component models. As such, for this project the company took on tasks that correspond to those of a BIM manager. The client initially only wanted a digital building model to be developed says Frank Rudolph, who took part in the planning as BIM administrator. “Then, however, we had to integrate the other specialist planners’ component models,” he adds. To this end the BIM modelers created a 3D model with the detailing and information level of a design plan and forwarded it to the specialist planners in IFC format. On this basis they subsequently developed their own component models and sent them back, again in IFC format, to the overarching BIM manager.

The BIM manager had the models analyzed for errors by means of collision checks, which, if there were any, were then eradicated during the revision process. At the end of Service Phase 3 the project planners handed over the coordination model with the integrated component models in the native data format to the general contractor. The latter was then able to use it to plan the construction work, and advance it. For architects, the migration of native, i.e., of the original data formats into the modeling software used, as opposed to the data transfer in IFC format (which like a PDF cannot be changed), entailed risks, Rudolph comments. Ultimately the entire office know-how was transferred with the native data, he adds. “It is important for the building model only to contain the information that is needed for the relevant stage in the project,” he says from experience. Moreover, in his opinion the German Fee Structure for Architects and Engineers (HOAI) needs to be amended to ensure that the transfer of data by architects to the experts handling the later Service Phases be remunerated as well, as the latter benefit greatly from the former’s preliminary work.

Sebastian Schöll also emphasizes the importance of contractual safeguards with regard to use of the building model. He also points out that even today the HOAI Service Phases can only in part reflect BIM. “Though 90 percent of the services covered by HOAI correspond to the level of development of BIM planning, time-wise they are structured differently,” Schöll says.

There were indications, he continues, that the HOAI Service Phasestage structure will be replaced by a few consolidated service components. Despite all the advantages BIM offers, Schöll is nonetheless worried that the planning culture might well be in danger. In their striving for greater efficiency, architects must not forget what constituted the basic evaluation in HOAI, he warns. Even with an extremely efficient design they can proportion a building correctly or incorrectly. Architects must therefore not stop considering what the right materials, combinations, and details are, he adds. It would also be wrong for clients to believe that BIM means architects are only needed for basic planning. In order to ensure the quality of a project in term of design and execution, in the future too, architects need to be in control of a construction project through to commissioning, Schöll explains.

This article is based on a text by Carsten Sauerbrei, Berlin, first published in our publication “Projects 6”, 2017

Frank Rudolph

Head of Digital Practice